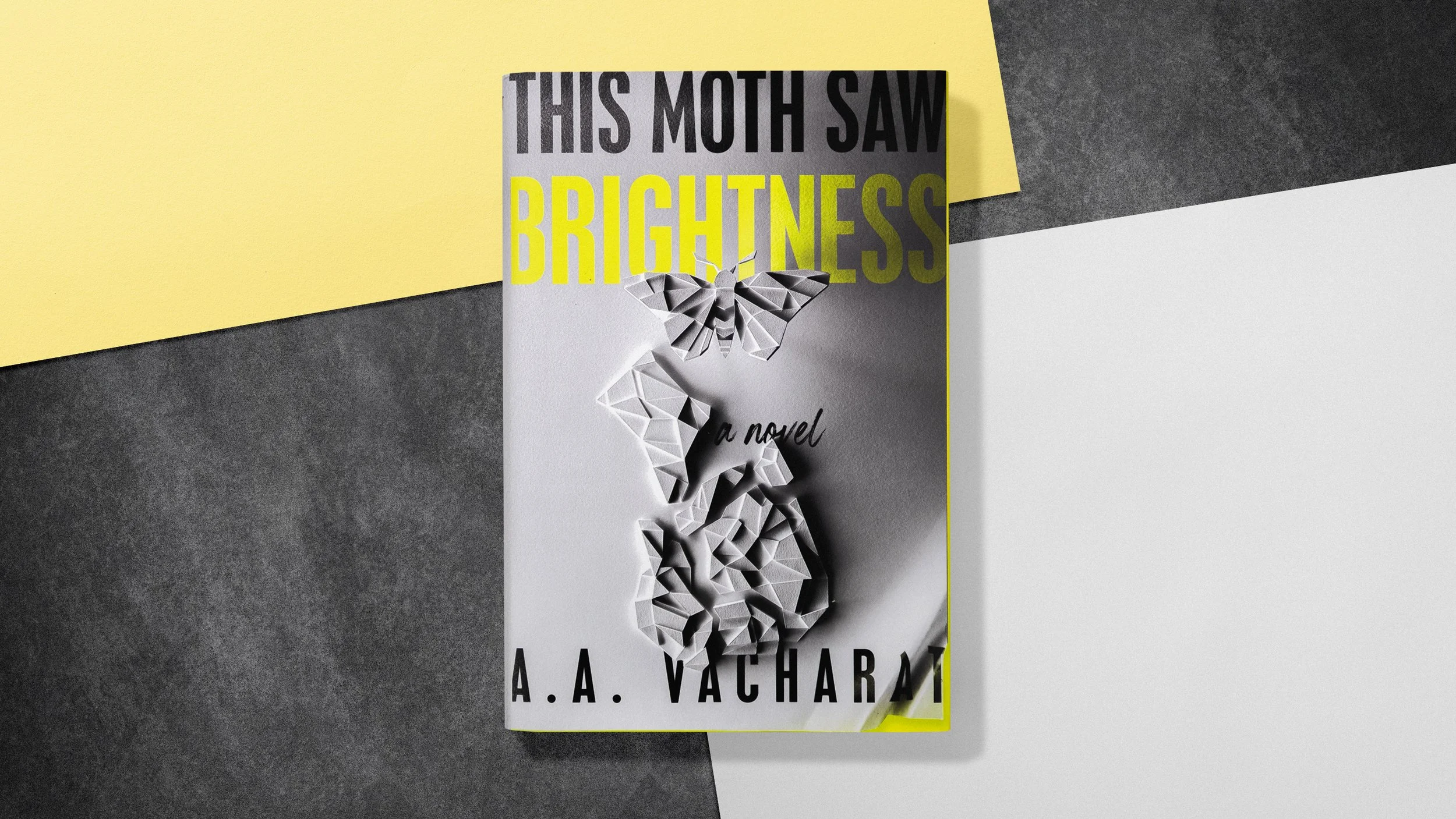

Book Club Discussion Guide for THIS MOTH SAW BRIGHTNESS

The following book club questions and discussion guides are free to use and edit.

I wrote the questions: they are not affiliated with Penguin Random House or Dutton Books.

Email me if you are interested in having the author (me) visit your book club or classroom via video chat.

Why is THIS MOTH SAW BRIGHTNESS one of the best book club books of 2025?

If your book club is looking for a novel that sparks real conversation, This Moth Saw Brightness is a great pick. Fast-paced and darkly funny, it’s an engaging read packed with deeper, often unsettling questions.

Here’s what makes it book club-worthy:

Expect strong opinions from your members. The novel’s tendency towards ambiguity, morally gray characters, and weirdly compelling (and also just weird) structure (including some bold craft choices) will provoke opinionated discussion in the best possible way.

Timely themes – Mental health, neurodivergence, conspiracy theories, institutional power, and who gets to be considered fully human. The current day relevance will make it easy for readers to bring in personal perspectives and real-world connections.

Genre-bending – The internet can’t decide on whether this book is a thriller, romance, mystery, sci-fi, or speculative satire. Maybe your book club can figure it out?

Different entry points –Whether your group leans political, emotional, philosophical, or likes to talk about writing craft, there’s an angle for every sort of discussion.

Craft choices some may love to hate – The structure is weird. Someone will hate it. Everyone will love to discuss it.

Ambiguity even on what’s ambiguous – No clear answers. Lots of clear questions.

Morally slippery characters – Complex people all trying their hardest, to varying degrees of success.

Fast pacing, plenty of white space – Even busy readers will finish in time.

Suitable for multi-generational book clubs— While published as a young adult novel, the sophisticated concepts and nuanced themes will appeal to adult book clubs as well.

An unforgettable ending – The kind that will haunt your book club’s chat group for years.

Not just vibes

GENERAL BOOK CLUB Discussion questions

D’s mental health, and whether he too is neurodivergent, are left unclear. What assumptions did you make about him? What effect did the lack of clarity have on your reading experience?

Much of the location and the world is slightly askew—it’s not quite Baltimore, and most of the adult characters aren’t quite believable. What effect does this have on the story? What effect does it have on your reading experience?

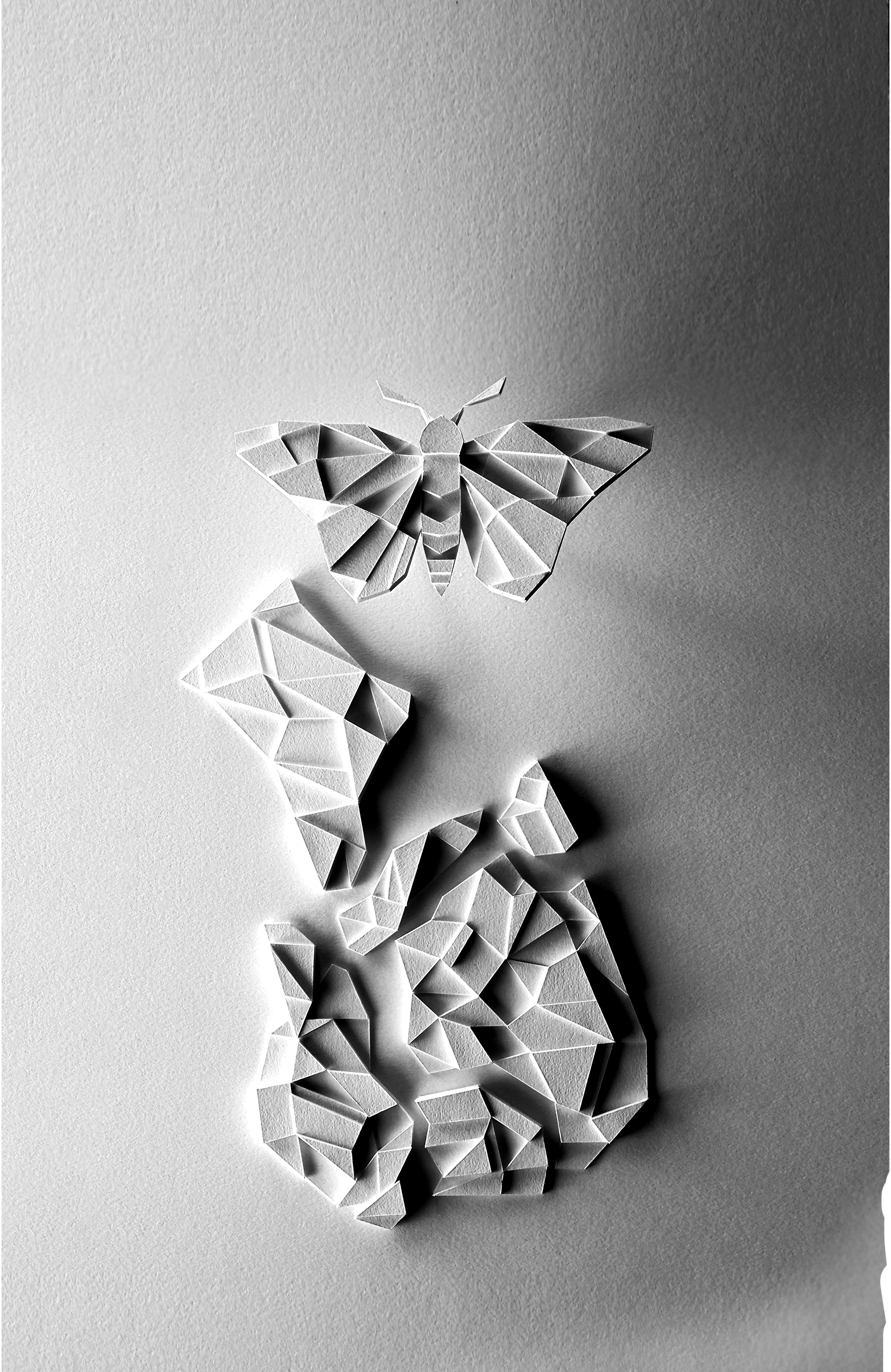

A moth “seeing” brightness can have both good and terrible connotations. Why might this have been the choice of title for this story?

Jane battles with the desire to love humanity while also believing humanity might have some inherently terrible tendencies. Which side of her do you think is winning? Where do you think she’ll end up on this continuum after this study? As she grows up?

In many ways, Kermit’s character conflicts with ‘Wayne’s. What do you think makes them friends? Why does their friendship work? (Or doesn’t it?)

The footnotes are tonally different from the rest of the novel. What effect did this have for you?

In Brechtian theater, breaking the fourth wall was a device that was meant to prevent the audience from ever fully forgetting that they were watching a work of fiction. What devices does this book use to mimic that technique? Does it successfully achieve this effect—or were you able to entirely “escape” into the fictional plot? What effect would keeping the reader distant have on their experience?

Towards the end of the book, Jane interrupts the narrative and inserts her own thoughts several times. She even disagrees with the primary narrator, ‘Wayne. Why might she do this? When she says this isn’t her story, do you agree with her?

The “author” mentions that how you choose to end the book depends on whose story you believe it to be. Whose story do you believe it to be? Who else’s story might it be, and, which ending goes with each?

Naomi’s articles/interviews often touch on what we do and don’t understand about what’s happening now. What do the voices disagree on? How do the themes these interviews bring up—either individually or as a whole—relate to the themes in the rest of the story? What are differences between what these voices say individually versus what they say when taken as a collective group that represents a country?

What do you think the study was about? Why?

Do you think the kids were onto something real, or chasing a conspiracy theory?

We live in a time period where conspiracies and theories about them run wild and control much of what people think or do. Often times, there is no way to know the Truth. In one of Naomi’s final interviews, the speaker says that “growing up is …* world bigger than you.” Which of the characters, if any, did you think most reached this point? Do you think this represents the character that is the most “grown up”?

Towards the end, the “author” floats the idea that perhaps something was going on with the Drone Wars video game. What, if anything, might have been going on? Is there any evidence for this in the course of the novel? Do you think that using a conspiracy theory to distract from the actual conspiracy is something that happens in real life?

How might a reader’s takeaway be changed if the story had a tidier ending? (E.g. If you learned what the study was about, and whether it was “good” or “bad”? If the mystery was “solved”? If you knew whether D was changed or not?)

How would you have ended it and why?

Like many things in this book, the question of whether D is actually changed by the pills is left unanswered. This ambiguity allows the question: how much can a person change and still be “themselves”? What do you think it means to be “yourself”? Does D change from beginning to end?

The Mary Oliver poem quoted in the beginning says “I was always running around looking at more and more.” How does this relate to the book? Who in this book is looking for more and more? And what is that more? How does it relate to people in our current times?

The poem goes on to say that if “I stopped, the pain was unbearable.” Do you think this is true of any of the characters in this book—that if they stopped keeping busy all of the time, the pain would be unbearable? What pain would they feel?

Why do you think these parts of American History aren’t typically included in this country’s narrative? Do you think they should be? Why/why not?

Conspiracy-specific BOOK CLUB Discussion questions

—for book clubs and readers who enjoy thinking about the real-world connections of the books they are reading.

This Moth Saw Brightness (May 2025) is a novel about ‘Wayne Le – a BIPOC, neurodivergent teen drawn into a “seemingly ordinary” medical study that spirals into an “M. C. Escheresque maze of conspiracies.” The book explicitly grapples with how “conspiracy theories and genuine conspiracies” can blur together, and how the inability to distinguish truth and reality colors how we process our own identity. Its themes – mental health, identity, the value of marginalized people, and the search for truth – resonate strongly with recent news about Jeffrey Epstein’s case.

In July 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and FBI announced after reviewing over 300 GB of Epstein case files that they found no secret “client list” or evidence of new crimes. This directly contradicted earlier claims by Attorney General Pam Bondi (who had teased such a list on Fox News) and fueled widespread confusion.

This swirl of conflicting statements – Bondi vs. DOJ, Trump fans vs. critics – mirrors the novel’s tension between hearsay and hard proof. As The Atlantic notes, the Epstein saga “hits on every theme of every major conspiracy theory” and has left people unsure “what’s real and what’s made up” .

The convergence of This Moth Saw Brightness and real-world conspiracy drama invites book clubs to explore how we discern truth, whom we trust, and how stories (fictional or factual) shape our view of justice.

Fact vs. Fear: In our current world, there is tension between two ways of responding to information—grounding yourself in what can be verified (fact) versus letting uncertainty and rumor drive your beliefs (fear).

In the Epstein ordeal, what parts of the conversation are actually grounded in truth? What information is grounded in someone’s agenda? Is there overlap between the two? In MOTH, ‘Wayne and his friends find clues but can’t be sure if the conspiracy is real. What are times that they are led by fact? When are they lead instead by imagination or feelings? When do the characters successfully separate credible evidence from wild rumor? When could they have done a better job? What evidence would the kids have needed to find to make you trust that the study was a genuine conspiracy? What would you need to make you completely sure it was all something in their heads? Given the information that actually exists in the novel, which do you think is more likely?Authority and Transparency: ‘Wayne volunteers for a study run by a “prestigious university.” His father implicitly trusts the people designated as experts, even though they are not fully forthcoming. In the novel, who or what resources do ‘Wayne and his friends trust? Why is ‘Wayne’s father so keen to believe in the American ideal; what would it mean to him if that ideal was an illusion? In the real world, what makes some people more willing to trust authority? How does the book portray consent and honesty in the study? How about consent and honesty between friends and family? How does that compare to the US government’s handling of the Epstein files? What parallels do you see between the trust the characters have for authority figures in the book and the trust from people in real life?

Information Literacy: MOTH uses a variety of documents and devices to tell the story: letters, excerpts of interviews, app assignments, ‘Wayne’s first person narration, Jane’s commentary, footnotes, and even a note from—allegedly—the author. Are all of the sources equally reliable? Are there indications that some sources are less reliable—and if so, what are they? What information is lacking potentially important context? What is the difference between a conspiracy and corruption? Or a conspiracy and lying?

Contradictions: When talking to people about conspiracy theories, often they will say or believe contradictory theories or have feelings. For example, someone might believe that vaccines cause autism, and that autism needs to be cured, even while also having many autistic friends and believing that autism isn’t a disease. In the novel, what contradictions do you see in the characters’ reasoning? Where does logic falter?

Social Media and Skepticism: MOTH shows teenagers (a generation steeped in endless information, AI deep fakes, and alternate reality meta-verses) grappling with half-truths. How do rumors spread in Wayne’s world? What role does each friend play (skeptic, believer, or something in between)? How does this compare to how conspiracies spread in the real world? How might being under 18 affect your ability to analyze the world around you?

Identity, Privilege, and Valuing Stories: Vacharat’s novel centers on ‘Wayne, an “invisible” second-generation immigrant in an American high school – and his second-generation friend Kermit, and his autistic female friend, Jane — raising questions of whose lives count, and whose stories are valuable enough to tell. How does MOTH address the worth of ‘Wayne’s family and peers versus the shadowy figures controlling the study? Do the characters in the novel recognize (and to what extent) that power and race affect whose side stories are told? In news coverage of conspiracies, how often do we hear the voices of victims compared to celebrities and elites?

Questions of Ambiguity: Ultimately, MOTH asks readers to consider the impact of ambiguity. One of the reasons conspiracies develop is a way to ease our brains’ discomfort with uncertainty—it creates patterns and reasons to connect things we do not understand to easy the discomfort. The novel’s ending (described as “deeply unsettling” by reviewers ) intentionally leaves some questions open. Similarly, many conspiracies remain incomplete and we may never have all of the answers—or even know when/if we have all of the answers. In MOTH, what kind of resolution do the characters seek? How do you feel about the book’s semi-open ending? How did you feel about the book’s ending—did the lack of explanation about the study make you uncomfortable? How would you have ended the book, and —if you would have changed it—what would that changed ending imply about real world conspiracies? Likewise, how do you think society should respond when official answers are unsatisfying? Whose story do you feel like this is?—Does the story belong to any one of the characters, or does it belong to a larger agency or structure of power? Is this story about getting the answer, or understanding what not having an answer can do to the way we think and feel about ourselves and the world around us?

Conspiracies & Information Literacy: Classroom Discussion questions

School Library Journal gave THIS MOTH SAW BRIGHTNESS a star and Booklist called it a great resource for starting discussions in classrooms about information literacy. How do we decide what information to trust? How do we know (do we ever know) what information is true?

Below is a discussion guide for the novel that is grounded in —and gives some general context about—the psychology of conspiracy theories. Please feel free to use, adapt and expand on these questions as you find useful!

1. Roots of a Theory

Humans have an intentionality bias (we assume big events are planned) and a proportionality bias (we expect things that have a big effect had to have had a big cause). In moments of uncertainty, pattern-seekers will attempt to fill gaps.

In MOTH, what first sparks ‘Wayne’s suspicion that something secret is afoot?

What evidence do we have that ‘Wayne is a pattern-seeker?

Can you pinpoint a scene where someone “connects the dots” with too little evidence? How might a proportionality bias be at play—does a character (or do you?) expect the study’s oddities to imply a grand conspiracy rather than mere oversight?

Think of a time you or someone you know saw a pattern in randomness (e.g., a coincidence on social media) that turned out to be nothing. What emotional need did that pattern serve in the moment?

2. Narrative Appeal

Conspiracy theories impose simple story arcs—heroes, villains, secret plots—because our brains crave clear narratives to reduce uncertainty and restore a sense of control.

Does MOTH conspiracy mirror the hero-villain structure? Does the explanation the characters come up with have a simple story arc?

Consider the motivation of each “villain” in the book. Is there any “gray area” that might be glossed over because a black-and-white narrative feels more satisfying? How does that compare to real-world conspiracies that simplify complex systems into single bad actors?

3. Community & Belonging

Sharing a conspiracy belief creates an “us vs. them” group identity and fulfills belonging needs—people feel special as “truth-knowers” and gain in-group esteem.

‘Wayne, Kermit, and Jane have very different personalities. How does the Hopkins Study give them a way to bond? Do you think they could have been friends without the shared theories? Are there times when ‘Wayne keeps going in the study because he wants a reason to keep talking to Kermit and Jane?

In what ways do the characters feel more empowered or energized when they believe they’ve discovered hidden truths? Can you relate to any moments where being part of a small “in-group”—a belief, an idea, an interest, or a way of speaking— gave you purpose or confidence?

4. Information Gaps & Authority

When authorities withhold information (redactions, official silence), people fill in blanks with their own explanations, often the most dramatic ones.

In MOTH, what key details are deliberately withheld from ‘Wayne, and how does that fuel his imagination?

What might a more transparent authority have done to prevent the spiral of rumor? Relate this to a real-world example—when have you seen an institution’s silence or partial disclosure spark wild speculation?

5. The Feedback Loop

Confirmation bias and early “hits” in a theory strengthen belief, creating a cycle: the more “clues” you find, the deeper you dig, even if those clues are random or coincidental. Furthermore, people tend to accept information that fits their worldview and dismiss what doesn’t. Analytical thinkers are less prone to conspiratorial beliefs than intuitive thinkers.

As ‘Wayne uncovers more ambiguous evidence, how does his confidence ebb and flow? Is there a moment you can pinpoint where he truly starts to believe? How did your feelings as a reader mimic ‘Wayne’s—did they follow his or did you have moments of disagreement? Is there a moment in the book where you became convinced this was a true conspiracy—or a moment where you became convinced of the opposite, that this was entirely in their heads?

Identify a moment when a character interprets a coincidence as proof. How might an awareness of confirmation bias have changed their reaction? Jane is aware of her own confirmation bias—she recognizes that because of all of her research, she wants to believe that she is in a government experiment. Does her self-awareness change her actions?

Which MOTH characters are analytical thinkers, and which are more intuitive? How does they challenge or reinforce each other?

Consider your own reading style—do you tend to question sensational elements immediately, or do you “go with your gut” first? Is this different for when you’re reading a novel versus when you’re looking at social media, or do you apply the same approach?

What mental shortcuts do we use to accept evidence that fits our world view and dismiss what doesn’t? How can you “check” yourself when reading sensational claims?

6. Conspiracies as Coping

In times of stress or helplessness, conspiracy narratives can restore a sense of meaning and control, acting as a psychological coping mechanism rather than a sign of pathology. However, they can also fracture relationships and lead to real-world harm if participants refuse to re-evaluate when evidence contradicts the theory.

‘Wayne lives with anxiety and a sense of invisibility. How might embracing a conspiracy theory serve as a coping strategy for his deeper fears?

When does that comfort cross into harmful territory—where believing the conspiracy makes him feel worse, isolates him, or distracts him from real solutions? At what point in MOTH do ‘Wayne’s theories begin to damage his friendships or his trust in himself? Can you draw parallels to how people sometimes latch on to conspiracy during crises (e.g., health scares, political upheaval)—is there a crossover point where people go from finding the conspiracy helpful to having it isolate them from their friends and family? Share an example—from news or personal life—where a conspiracy belief backfired on a community— led to broken trust, damaged reputations, or real-world harm. What warning signs appeared before things went too far?

7. Storytelling & Power

Controlling the “official story” is a form of power. Those with access to documents, footnotes, or media platforms can shape collective belief; dissenting voices struggle for visibility.

Who in MOTH has the power to shape the study’s official narrative?

This novel uses devices to break the fourth wall, including a note from “the author.” What effect does this have on your processing of the novel as being its own document? What might this imply about the “author’s” role in shaping what you believe and how you feel?

In our media landscape, which institutions or influencers hold narrative power—and how do “alternative” voices fight to be heard? Relate this to a moment when a whistleblower or independent journalist disrupted a dominant storyline.

8. From Fiction to Reality: Takeaways

Understanding the cognitive and social roots of conspiracies can help us guard against misinformation in our daily lives.

After reading MOTH and learning about biases, coping motives, and group dynamics, what mental habits or discussion “best practices” will you adopt?

How might you as an individual pause and assess sensational claims next time you encounter them online or in conversation? What concrete steps (e.g., check multiple sources, ask “Who benefits from this story?”) can you put in place?